This miniature portrait on enamel is by Jean Francois Soiron (1756-1813) a Swiss artist who worked in Paris and was noted for his enamel portraits.

This miniature portrait on enamel is by Jean Francois Soiron (1756-1813) a Swiss artist who worked in Paris and was noted for his enamel portraits.It is set into the top of a green lacquer snuff box with gold inlay (apologies for the scanner glare) and the miniature itself is only 43mm in diameter.

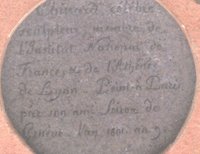

The counter enamel is inscribed "Chinard celebre sculpteur membre de l'Institut National de France, & de l'Athenee de Lyon. Peint en Paris par son ami Soiron de Geneva Van 1801 an 9". (Chinard, celebrated sculptor and member of the National Institute of France and the Athenum of Lyon. Painted in Paris by his good friend Soiron of Geneva in 1801, year 9).

Dating of the miniature is interesting as it is dated in both the normal calendar as 1801, and also in the French Revolutionary Calendar which commenced in 1792, thus "an 9" was 1801.

Dating of the miniature is interesting as it is dated in both the normal calendar as 1801, and also in the French Revolutionary Calendar which commenced in 1792, thus "an 9" was 1801.The Bourgeois miniature in this collection is also dated "an 9".

Enamel miniatures by Soiron are rare, but for another example of a miniature by him see Jean François Soiron - Museum Briner und Kern

Joseph Chinard (1756-1813) was a famous French sculptor. This miniature is believed to be the only contemporary portrait of Chinard and hence is an important historical item.

Although the image itself does not appear, this miniature of Joseph Chinard is described in the book; "Les Peintres en Miniature actifs en France 1650-1850". The reference is towards the end of the section illustrated here.

Although the image itself does not appear, this miniature of Joseph Chinard is described in the book; "Les Peintres en Miniature actifs en France 1650-1850". The reference is towards the end of the section illustrated here.The Frick Museum describes Chinard as one of the greatest portraitists of 18C and early 19C France, see ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION

Acquired subsequently for this collection, was this medal of Joseph Chinard by Torcheux.

Acquired subsequently for this collection, was this medal of Joseph Chinard by Torcheux.The obverse and reverse views of the medal are shown here with the obverse depicting Joseph Chinard.

The reverse depicts Chinard's famous sculpture of the Empress Josephine which is in La Malmaison.

The medal is 67mm in diameter and is signed "A H Torcheux", for Andre-Henri Torcheux (1912-?) who is shown in the photo.

The medal is 67mm in diameter and is signed "A H Torcheux", for Andre-Henri Torcheux (1912-?) who is shown in the photo.Torcheux seems to have made a number of medals commemorating various prominent French citizens from the 19C and 20C.

At present the actual date and the reason for striking this medal is unknown.

A bust of the Empress Josephine was sculpted in Milan in 1805 when she accompanied Napoleon to that city for his coronation as the King of Italy.

A slightly different terracotta version, with shoulder ruffs on the dress, is currently housed in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio.

For more about Chinard, including details of his works in the Getty Museum see Joseph Chinard (Getty Museum)

Also shown here is another miniature portrait by Jean-Francois Soiron. This one of Napoleon was displayed in an exhibition at Somerset House entitled 'France in Russia : Empress Josephine's Malmaison Collection' which ran from 25 July to 4 November 2007.

Also shown here is another miniature portrait by Jean-Francois Soiron. This one of Napoleon was displayed in an exhibition at Somerset House entitled 'France in Russia : Empress Josephine's Malmaison Collection' which ran from 25 July to 4 November 2007.The exhibition explored the history of Empress Josephine’s Malmaison collection, purchased by Alexander I in 1815 and now held by the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia. 884

More about Joseph Chinard

Born in Lyon on February 12, 1756, Chinard entered the studio of Barthélemy Blaise (1738-1819) around 1770. By 1880 he had received commissions for statues of The Four Evangelists for the Church of St. Paul in Lyon (destroyed) and other religious works followed. An early Narcissus in marble, is reproduced in Les Arts (November 1909), along with The Death of the Centaurs and several other works. Baron La Font de Juys, a patron of Pierre Julien (1731-1804), advised Chinard to study in Italy and provided the funds for him to do so. In return, Chinard finished copies of Antique originals: Bacchus, Ariadne, Homer, Germanicus, etc., while he was in Rome (1784-87). In addition, he entered a competition at the Accademia di S. Luca, submitting a first prize-winning terracotta Perseus and Andromeda (several versions are known: see Rocher-Jauneau, 1961 and Worley, 1989).

A profile portrait medallion of Louis XVI, signed and dated 1789, suggests that Chinard did not immediately take to the Jacobin ideas that were blowing in the wind. However the sculptor erected a colossal statue of Liberty a year later on the occasion of the Fête de la Fédération, then returned to Rome in 1791 where he developed new and highly radical Revolutionary themes, such as Jupiter Striking Down Aristocracy and Apollo Trampling Superstition at His Feet (both from 1791; Musée Carnavalet, Paris). The latter was considered to be an outrage against the Catholic Church since Chinard chose a veiled female figure of Religion (complete with a crucifixion) to represent Superstition. Chinard was arrested in the middle of the night and thrown in the Castel Sant’Angelo in September of 1792. Back in Paris, Chinard’s wife alerted Jacques-Louis David who appealed to the Convention, then the papal authorities were warned by the French Republic. Chinard was released but had to leave Rome immediately. Later he would receive an indemnity for the possessions he had to abandon. Yet apparently, his terracottas were not proof enough of his republican zeal, for his subsequent works in Lyon were overly scrutinized. For example, the figure of Liberty, carved for the pediment of Lyon’s City Hall, was criticized for holding a civic crown too far back into space, and his statue of Fame was misinterpreted as summoning the emigrants to return from Switzerland. Again Chinard was placed under arrest (1793). While in prison, he modeled Innocence Taking Refuge in the Bosom of Justice (unlocated), sort of an artist’s statement of self defense, then he was acquitted. No wonder Chinard decided to specialize in portraiture.

In 1795 Chinard was elected to the Institut, though he continued to reside in Lyon. He continued to produce portraits, light mythological themes and Revolutionary allegories. Only a few of his many portraits (including numerous medallions) can be listed here; the reader is urged to consult Lami’s catalogue and Rocher-Jauneau’s many articles. The latter, still regarded as the Chinard authority, states that Chinard’s portraits are marked by “a sensitive and very personal realism.” There are several portrait busts of Napoleon, Josephine (Château de Malmaison), Prince Eugène de Beauharnais, General Desaix (Salon of 1808), Empress Marie-Louise, and fellow artists (Girodet, Boilly, Isabey). The Rhode Island School of Design has Chinard’s marble bust of Madame Récamier (1802). The sculptor was named professor at the Ecole spéciale de Dessin in Lyon in 1807. On 20 June 1813 Chinard passed away. He would be remembered as one of the greatest portraitists during the French Empire and Lyon’s premier Neoclassical sculptor.

Sources:

De la Chapelle, Salomon. “Joseph Chinard, sculpteur, sa vie et ses oeuvres.” Revue du Lyonnais 2 (1896): 77-98, 272-291, 337-357 (1897): 141-157; Tourneux, Maurice. “La collection de M. Le comte de Penha Longa.” Les Arts (November 1909); Saunier, Charles. “Joseph Chinard et le style Empire à l’exposition du Musée des Arts Décoratifs.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts (January 1910); Schwark, Willi G. Die Porträtwerke Chinards. Freiburg-im-Breisgau, 1929; Dorner, Alexander. “Portrait Bust of Mme. Récamier.” Rhode Island School of Design Bulletin 26 (1938): 13-19; Zimmermann, H. “Joseph Chinards Terrakottabüste von Mme Récamier.” Berliner Museen 7 (1957): 42-47; Rocher-Jauneau, Madeleine. “Persée et Andromède de Chinard.” Bulletin des Musées et Monuments Lyonnais (1961): 350-352; Boyer, Ferdinand. “Projet d’un monument de la Victoire par Chinard pour Marseille en 1812.” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français (1962): 263-264; Rocher-Jauneau, Madeleine. “Chinard and the Empire Style.” Apollo 80 (1964): 220-226; Perez, Marie-Félicie. “L’exposition du ‘Sallon des arts’ de Lyon en 1786.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 86 (December 1975): 199-206; Rocher-Jauneau, Madeleine. L’oeuvre de Joseph Chinard au Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. Lyon: 1978; Skulptur aus dem Louvre. Exh. cat. Duisburg, 1989, cat. nos. 68, 84, 87; Worley, Michael Preston. “Persée et Andromède de Chinard: Une fausse attribution?” Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France (October 1989): 249-252; Rocher-Jauneau, Madeleine. “Chinard, Joseph.” From David to Ingres: Early 19th Century French Artists. The Dictionary of Art series. London and New York: Grove Art, 2000, pp. 54-55.

No comments:

Post a Comment